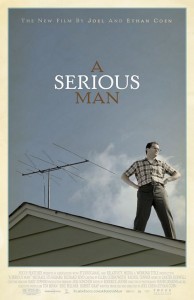

The Coen brothers can be obtuse filmmakers: operating as if to apply their master’s touch on mainstream films solely for building the studio goodwill needed to produce the films they’re really interested in making. Such is the case with A Serious Man. It’s not mainstream. It’s not even midstream. Critics will love it, but the general audience won’t see it and those who do will find it totally, inaccessibly boring. Which doesn’t mean it’s bad- it just means A Serious Man is a labor of love. It’s not for anyone but the Coens. If you happen to get on board, well, then all the better.

The Coen brothers can be obtuse filmmakers: operating as if to apply their master’s touch on mainstream films solely for building the studio goodwill needed to produce the films they’re really interested in making. Such is the case with A Serious Man. It’s not mainstream. It’s not even midstream. Critics will love it, but the general audience won’t see it and those who do will find it totally, inaccessibly boring. Which doesn’t mean it’s bad- it just means A Serious Man is a labor of love. It’s not for anyone but the Coens. If you happen to get on board, well, then all the better.

As is the Coen’s usual, A Serious Man brims with sociological ribbing. It’s a Jewish-themed parable, a dark comedy, an existential faith exploration, a look at good guys finishing last and a filmic high five to the concept that life sucks and then you die. But beyond the standard Coen quirk, it’s just not 110 minutes interesting.

Larry Gopnick (Michael Stuhlbarg) is a good guy. Unfortunately, a hundred years or so previous, his ancestors made the foolhardy decision of allowing a dybbuk– a wandering spirit– into their home. Thanks to the sins of his fathers, Larry is now destined to live a life duly cursed– a delinquent son, an unfaithful wife, legal woes, multi-faceted job drama, a car crash, a pathetic, live-in brother and a faith that isn’t doing much to help him make sense of it all. All this sandwiched between two neighbors: one a scary, gun-toting man’s man, the other a lonely and willing Cougar.

Larry Gopnick (Michael Stuhlbarg) is a good guy. Unfortunately, a hundred years or so previous, his ancestors made the foolhardy decision of allowing a dybbuk– a wandering spirit– into their home. Thanks to the sins of his fathers, Larry is now destined to live a life duly cursed– a delinquent son, an unfaithful wife, legal woes, multi-faceted job drama, a car crash, a pathetic, live-in brother and a faith that isn’t doing much to help him make sense of it all. All this sandwiched between two neighbors: one a scary, gun-toting man’s man, the other a lonely and willing Cougar.

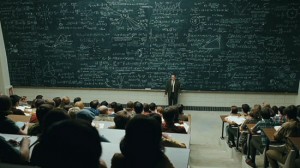

All the suburban bedlam is pure irony, as Larry spends all day transcribing incredibly complex equations explaining the order of the universe as a physics professor at a local university. Like a watered down, scriptural Job, Larry can’t explain his own chaos. He seeks counsel from an endless procession of rabbis who can’t explain it either, each resorting to various go-to religious cliches in the attempt.

The story unfolds by stacking one problem after the other, each shouting for attention in their freneticism. Larry’s only escapes are played out in increasingly vivid dreams where his id gets the better of him, but Larry is too interested in being the good guy– the civil guy– to take much action in real life. Even when Sy Ableman (Fred Melamed), the man who’s stolen Larry’s wife and seeks Larry’s support for religiously sanctioned divorce, suggests Larry leave his house so he can move in and make things “good for everyone”, Larry rolls over and acquiesces. He’s a hopeless cause really, and Larry labors through the abuse hoping for the best in a theologically underpinned ideal to be “a serious man” while resolutely taking all the beatings life has to offer.

The story unfolds by stacking one problem after the other, each shouting for attention in their freneticism. Larry’s only escapes are played out in increasingly vivid dreams where his id gets the better of him, but Larry is too interested in being the good guy– the civil guy– to take much action in real life. Even when Sy Ableman (Fred Melamed), the man who’s stolen Larry’s wife and seeks Larry’s support for religiously sanctioned divorce, suggests Larry leave his house so he can move in and make things “good for everyone”, Larry rolls over and acquiesces. He’s a hopeless cause really, and Larry labors through the abuse hoping for the best in a theologically underpinned ideal to be “a serious man” while resolutely taking all the beatings life has to offer.

The Coen brothers are in usual form here. Quirk abounds, “gotcha” violence is used as punctuation and characters are deadpan serious– all subtly played with light frivolity and an undercurrent of gallows gloom. Michael Stuhlbarg is believably funny and sympathetic in his portrayal of the perpetual good-guy schlub, but it’s the paint-drying equivalent of watching a dull life played out onscreen.

A Serious Man is a film asking for repeated viewings, but is also one whose initially dry deliberation intentionally creates a barrier to entry. A Serious Man is pinpoint accurate in its dour observation and poker-faced delivery (truly–there are perhaps a mild chuckle or two to be found here- nothing more), but in a world where most middle-agers have had a year spent absorbing as much abuse as Larry does, it’s just not that compelling.

A Serious Man is a film asking for repeated viewings, but is also one whose initially dry deliberation intentionally creates a barrier to entry. A Serious Man is pinpoint accurate in its dour observation and poker-faced delivery (truly–there are perhaps a mild chuckle or two to be found here- nothing more), but in a world where most middle-agers have had a year spent absorbing as much abuse as Larry does, it’s just not that compelling.

A Serious Man has me at a crossroads. The more I reflect on it, the more I find to appreciate, but the initial viewing didn’t garner the same enthusiasm. And when the film abruptly ends amidst a literal whirlwind of portending doom while Jefferson Airplane asks “Don’t you want somebody to love, don’t you need somebody to love”, most viewers will probably answer by nodding their heads in agreement.

1 comments On Move Review–Dan: A Serious Man (C)

Pingback: Award Season: A Serious Man | ()

Comments are closed.